Recent Posts

- considerations on formulating lab documents specialized clinical insider report making clinical article help out – ?13/document

- Explaining Youngsters Destruction

- Artificial intelligence: can it at any time have a site of human brain?

- E-commerce is surely an essential tool for your advancement of the service.

- Future Issues for Medical Treatment Management

Archives

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- February 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- August 2014

- June 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- September 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- February 2011

- December 2010

- July 2010

- January 2010

- February 2007

- March 2005

Categories

- 123esayessay.com

- academic paper

- Americas

- analysis

- Asia

- assignment

- aufsatzmeister.de

- Bdlollar

- Biomass energy financing

- Brazil

- Breaking-News

- Business

- buy dissertation

- buy research papers

- Careers

- CDR or Corporate Debt Restructuring

- China

- communication

- Custom essay

- custom essay UK

- Custom Essay Writing

- custom writing

- custom writings

- dai bog

- Debt and equity financing

- Debt and equity financing

- Diplomarbeit

- dissertation help

- Education

- Education News

- Education Review

- Energy

- ENGINEERING

- essay writer

- essay writing service

- essay-online.net

- Europe

- Events

- fast essays

- Finance & Accounting

- finance jobs

- Germany

- Get Essay

- ghostwritingfinden.de

- historic

- homework

- homework help 247

- India

- internet

- literature

- M&A

- macroeconomic

- management

- Middle East

- online essays

- pay for essay

- pay for essays

- Private Equity

- Private Equity

- private equity

- Private Equity

- Private Equity

- private-equity

- Project finance

- Quality

- rapid essays

- research paper help

- research paper writing

- Risk

- slider

- sociology

- Switzerland

- Technology

- UK

- Uncategorized

- Uncategorized2

- US

- Venture Capital

- Wind energy financing

- Новая папка (2)

India Utility Lanco Seeks Investors for 500 MW Expansion

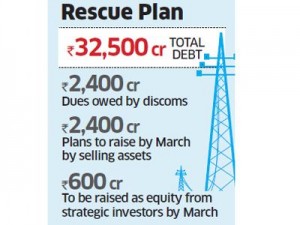

Debt Restructuring at India’s Lanco Infratech

Lanco Infratech Ltd., India’s second-biggest non-state power generator, is seeking private-equity investors to help expand its solar capacity fivefold as a coal shortage roils its thermal business and payment defaults by state utilities widen the group’s losses.

“The political intent in India is very strong,” Saibaba said, speaking from his office in Gurgaon near New Delhi. “Constraints like coal availability and fuel import bills will ensure India will have to focus on renewable energy.”

Lanco is joining Tata Power Co., India’s biggest non-state utility, which said Feb. 5 that it is scouting for investors and planning to sell shares at its solar unit as India extends grants to cut solar project costs and ease curbs on equipment imports. A plan announced last year by the Lanco group to raise $750 million selling stake in its conventional power unit to private-equity funds has stalled amid losses that have surged nine times in the first three quarters of the financial year.

The chairman of Lanco Infratech Madhusudhan Rao said he is ‘not averse’ to selling even a majority stake to an investor, provided the asset gets the right value.

Losses Widen

Shares of the New Delhi-based company have slumped 86 percent from a record reached on Dec. 28, 2007 to 11.50 rupees in Mumbai, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The slide in the value has eroded the wealth of Chairman L. Madhusudhan Rao, who was a billionaire as late as January last year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

“Lanco hasn’t done well when it comes to the power business,” which suffers from fuel supply problems, said Gaurav Oza, Mumbai-based analyst at GEPL Capital Pvt. “They seem to have done much worse in managing utilities as compared to their earlier success in construction.”

Lanco reported an annual loss of 1.1 billion rupees ($21 million) for the group in the year ended March 31, its first since its shares started trading in November 2006. The combined loss in the three quarters ended Dec. 31 climbed to 9.9 billion rupees, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

State-owned regional electricity distributors, often forced to sell energy below costs, are unable to pay producers as the difference between the cost of supply and average tariff has widened. The utilities had debt of 1.9 trillion rupees as of March 2011, government estimates show, even as lenders tightened credit. That has resulted in poor cash flows for Lanco.

Debt Outstanding

The company has 35 billion rupees of receivables, Rohit Sanghvi, an analyst with Prime Broking Co. in Mumbai, wrote in a Feb. 15 report. The outstanding amount is more than Lanco’s market value. Total debt stood at 95.7 billion rupees, of which the solar unit accounted for 5.5 billion rupees.

Lanco may be counting on interest in solar projects as the government targets to build 9,000 megawatts of grid-connected solar plants by 2017, more than eight times its current capacity. Solar-power producers are assured payments through letters of credit and escrow mechanisms set up by state governments, according to Saibaba.

With costs for alternative energy projects coming down, the tariff for solar and thermally produced electricity may reach parity in about three years, Saibaba said.

Interest Costs

Better potential realization is also helping lenders offer cheaper credit for solar producers, said Satnam Singh, chairman of Power Finance Corp., India’s biggest state lender to electricity utilities.

“We cut lending rates for renewables this month because we see better returns in the near future,” Singh said in an interview. Of the 23.7 billion rupees sanctioned by Power Finance to renewable companies in the year ending March 31, 15.8 billion rupees was to Lanco Solar, he said.

Solar companies have to pay interest rates as high as 13.5 percent to 14 percent in India, Saibaba said. The weighted average cost of debt for NTPC Ltd., the nation’s biggest power producer, was 8.6 percent according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

India’s policy draft released in December said the government would for the first time fund the solar industry with direct grants covering as much as 40 percent of the upfront cost of building projects. That model has previously been used to build roads, ports, railways and fossil-fuel power plants in India.

Slow to Fund

Private lenders have been slow to fund solar because of a lack of confidence in the technology, according to the draft. Solar companies in India sell power to state utilities which in turn cannot recover their costs from customers who buy power at lower rates.

Lanco will add 90 megawatts of solar capacity by the end of the fiscal year ending March, including a delayed 75-megawatt photovoltaic project for the local state-owned utility in the western Maharashtra state that it won in May 2011, he said.

Another 100 megawatts of capacity being built using solar- thermal technology in northern Rajasthan state has been delayed by a year, Saibaba said. The project, awarded under the first phase of India’s solar auctions in 2010, had to be reengineered to make allowances for differences in radiation levels and delays in getting heat-transfer fluid from U.S. suppliers, he said.

‘Still Grasping’

Lanco Solar is completing a manufacturing plant that will be able to produce 1,800 tons of polysilicon, 100 megawatts of ingots and wafers and 75 megawatts of modules a year, Saibaba said. The company expects to increase that capacity to 250 megawatts of modules annually in three years, he said. The total cost of this plant is 13.4 billion rupees of which 70 percent has been funded by loans, he said.

Private investors may look at the government’s commitment to support alternative energy sources before pledging any funds, said Mahesh Patil, who manages $2.5 billion in equity as co- chief investment officer at Birla Sun Life Asset Management Co. in Mumbai.

“Investors the world over are still in the process of grasping the business dynamics of solar-power developers,” Patil said. “Secondary markets, at least in India, aren’t yet ready to support share sales by renewable-energy companies.”

Recent Articles

- considerations on formulating lab documents specialized clinical insider report making clinical article help out – ?13/document

- Explaining Youngsters Destruction

- Artificial intelligence: can it at any time have a site of human brain?

- E-commerce is surely an essential tool for your advancement of the service.

- Future Issues for Medical Treatment Management

Recent Comments